Companies with one or more subsidiaries are required to publish accounts for the group of companies as a whole as well as their own annual accounts (s.399 CA 2006). This is because (subject to certain exemptions) shareholders of the parent company should have access to some information regarding the subsidiary company. In principle, every subsidiary in the group also has a duty to prepare its own individual accounts, but exemptions are widely available so it is likely to be rare in practice for subsidiaries to do so (ss.394A and 479A CA 2006).

In this post, I discuss the concept of consolidated accounts at a high level, without considering the rules in any detail.

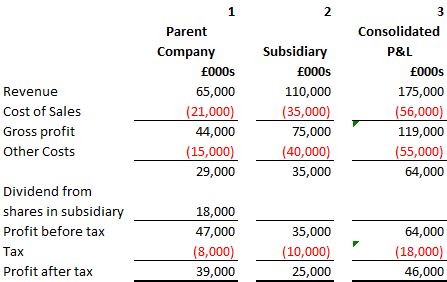

The consolidated Profit and Loss Account

In consolidated accounts, the Profit and Loss Account of the parent company and its subsidiaries are brought together (see the third column in the example below).

The Profit and Loss Account of the parent company (column 1 above) will include dividends paid to it by the subsidiary but not the subsidiary’s profits. Such dividends and any intra group trading that has taken place between the subsidiary and the parent company are excluded from the consolidated Profit and Loss Account (column 3 above).

There is one further factor to consider if the subsidiary is not wholly owned (i.e. if there is a third-party minority interest in the subsidiary). In this scenario, the entire profit for the parent company and its subsidiaries will be shown in the group accounts – then the minority interest’s share is deducted.

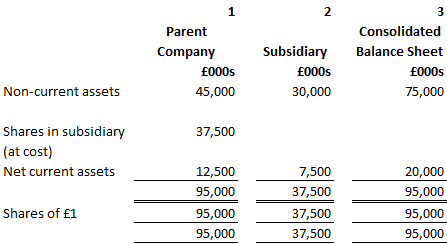

The consolidated Balance Sheet

The Balance Sheets of each company in the group will be amalgamated and the only issued share capital represented on the consolidated Balance Sheet (column 3) will be that of the parent company.

The Balance Sheet of the parent company will include the share capital of the subsidiary as a long-term investment, at cost. The subsidiary in this example has no subsidiary of its own and so shows no long term investment in its Balance Sheet (Column 2).

The assets of the subsidiary must however be added to the assets of the parent and represented in the consolidated Balance Sheet accordingly. After a subsidiary has been acquired, its profits are included in the consolidated Profit and Loss Account.

What if the subsidiary is not wholly owned? The total assets and liabilities of the companies in the group are shown, along with the minority interest’s share in those assets and liabilities as a deduction.